- David

Okay. So, my name's David Fox. I'm 64, almost 65.

And I've been involved in the game industry since the late 1970's. So, that's close to 40 years, and I was one of the first people hired for Lucasfilm Games back in 1982, and was there for 10 years.

- David

Yeah. I've seen that you're either employee No. 3 or No. 6.

- David

I guess I was No. 3, but sometimes I say No. 2.

- David

I saw that also.

- David

I was the second outside employee hired. There was a guy hired to run the group, then a guy transferred from the computer division -- which was our parent group -- into games. And then I was hired. So, I'll just leave it at three.

I was hired as a game designer programmer. I don't know who started this, whether Atari came to Lucas -- they already had a relationship because Atari had licensed Star Wars for the arcade.

So they'd already been working together for a few years. And what I understand is that Atari gave Lucasfilm a million dollars as seed money for this new games group with the idea that they would get right of first refusal. It was a given that we would be doing this development on Atari computers. The idea was that we'd do something first for the VCS 2600 and we pretty soon said, "You know, that's really gonna be limiting. Let's go for the 5200/Atari 800." And they agreed, and that's where we focused our energies.

- David

I know you're working on a project now, but I got the impression from our emails that you don't really think about the game industry anymore?

- David

Yeah. I mean, I feel like I'm kind of peripheral to it.

- David

Yeah. Why do you feel that way?

- David

I mean, I was definitely in it back in the '80s and maybe early '90s and then just kinda got sidetracked into doing other stuff. Maybe emotionally there was definitely still a connection.

But I pretty much missed what was happening in the games industry in the '90s and a lot of the 2000's. And since I never really went back to work in a large company, it was always from kind of an outsider point of view. I mean, I still had friends who were involved throughout the whole thing, so followed along with them to some degree.

The direction I was much more interested in than home gaming -- and this was even before I went to Lucas -- was much more location-based entertainment. The idea of a large-scope interactive Disneyland, where everything was immersive. This was before VR, though there already were flight simulators and -- did you ever read the book Dream Park? Ever hear of that book? Dream Park was by Larry Niven and Steven Barnes. Their idea of an environment where -- I guess the closest thing I've seen to this in a movie would probably be Hunger Games, except there you could die. [Laughs.] And in Dreampark everything was simulated. Also, I guess, Orson Scott Card has a whole bit about this level of gaming in Ender's Game.

- David

Oh, sure.

- David

That was kind of the intent for me. Really what Orson Scott Card wrote about was the idea of a game that knew you enough to actually help you grow and change and be different in some way. So, the idea wasn't just for fun, it was also to feel like you've gone through something transforming.

- David

Yeah.

- David

Back in the early '90s I was talking about lucid dreaming as something that's analogous, where you have a very real experience while you're asleep but you're still conscious. If you have a monster come at you, you could actually transform the monster or overcome the monster in the same way you would if you're playing an adventure game. When you wake up, you'd feel like you had accomplished something huge and you felt really different, transformed. And that was kind of my impetus for getting into gaming to begin with, looking to create more of a transformational kind of experience. So, in the early '90s, I was still at Lucasfilm and we ended up doing this location-based entertainment project, Mirage, which was kind of why I originally joined the company, with the hope that that would happen.

I got to work on Mirage for a couple years, but unfortunately at the time the tech was just too expensive for even a theme park and the project got shut down. After having a taste of that kind of immersion I just had a hard time going back to doing 2D adventure games. [Laughs.]

Mirage was a partnership between Lucasfilm and Hughes Simulation -- they did all the professional flight simulators for the airlines and military. They did the hardware, projectors, and a lot of the programming and we did the physical design and the game design part of it and it was really cool. Like I said, it was really immersive. You're in this two-seat cockpit -- more like a small room -- with a huge window in front of you that was 120-degree field of view and of partially wrapped around. It was being driven by three video projectors that were seamlessly integrated so you didn't see the line where they connected, where their images touched, and that combined image was bouncing off a collimating mirror so that your eyes are focusing at infinity instead of, like, five feet away. It wasn't 3D. There was no motion. But you still had the feeling that you're flying through these vast landscapes. I basically designed a game that was essentially Rescue on Fractalus! on steroids, you know, mountainous terrain and canyons, but it was in the Star Wars universe. It was just very cool. Multiplayer. There were other pods. The idea were there would be eight of these pods playing together or 16 people, two in a pod. One would be the gunner, and the other the pilot. After doing that and actually experiencing it, it was just kind of like -- yeah, I just couldn't picture going back to doing home games at the time.

- David

This may not sound exciting to talk about, but I'm curious to hear about the beginnings of game projects and how that has changed over the years. What were the beginnings of projects like in those days? How did you decide what you were going to do and what was that process like?

- David

Well, let me talk about our first two projects -- my game, which turned out to be Rescue on Fractalus! and David Levine's game, which ended up being Ballblazer. Initially we were told to do kind of experimental games. The idea was that these were throwaway games. There was no time limit to come up with something interesting. And if it was good, we would take it through to marketing and production to sell, and if not we would just toss it and start over. The idea was to start on a learning curve to get to know each other, get to know the process, get to see what we could do to push state of the art.

Peter Langston, our employee No. 1, was hired to be the manager of the group. His background was much more in the area of research and he was known for his PSL -- his initials -- tapes. They were magnetic computer tapes that made the rounds to all the colleges to play on their Unix machines. They were mostly text-based games that he wrote. The computer division itself was pretty much a research group. So, that was kind of the orientation of our group. We were a research games group inside the computer division, which was a research group inside of Lucasfilm, which was a film company.

We wanted to see what we could do to push the state of the art. Peter intentionally did not hire people with any experience in large computer game companies. For example, he didn't go to Atari and hire people who made arcade games, or he didn't go to Parker Bros. or Williams or some other arcade company. He wanted people who were doing games, were interested in games, but hadn't been spoiled by some corporate culture that kind of pre-established how we would look at the whole problem. So we built the culture up from scratch from within the computer division, which already had that research bent.

- David

Yeah.

- David

So, for the first two games there really was more of a research feel to it and experimenting and trying to see what we can do to see something different. I was really lucky to end up with Loren Carpenter from the computer division as my officemate for my first three or four months, until they had our own space ready to go. I had met Loren a year earlier when I was doing research for my Computer Animation Primer book when I got to talk to Loren and others from the computer division. This was, again, a year before the games group was started. That might have been part of why I ended up with a job -- I already had a connection with them, so it was easy to make the phone call and get an early interview. And the way I heard about it was from a member of our computer center. My wife, Annie, and I had this non-profit public access microcomputer center in Marin and people would come to rent time on our microcomputers. That's where I got my experience programming games, by converting games for other companies, like Adventure International, who would pay us a royalty for the conversion -- for example, converting the game from the Radio Shack TRS-80 to the Apple II.

- David

Yeah.

- David

And so one of our members who worked at ILM -- Industrial Light and Magic -- said, "Hey! Did you hear there's going to be a new games group starting at Lucasfilm?"

I had already met Ed Catmull, the head of the computer division, while working on Computer Animation Primer, so I called him up and said, "I would really like to get a job there doing games." He introduced me to Peter and a few months later, I got the job.

So, because I was office mates with Loren Carpenter and Loren was the guy who came up with the first 3D flight through a fractal environment in a movie, he was essentially Mr. Fractal. He was the fractal whiz. And pretty soon after I started I said, "Hey, is it possible that we could do some kind of fractals on an Atari computer?" His first response was laughter. He said “No, you couldn't do that.”

And then he started thinking about it and said, "Well, maybe there is a way to do something." Nothing close to what he would do on a high-end computer. On those, it's not real time. You're taking hours to render each frame and here we had to do something on a tiny microcomputer at a fast enough frame rate to actually get motion. So, a huge difference but he knew the concept enough to figure out what we could get away with. We loaned him an Atari 800, a book on assembly language, he taught himself 6502 Assembly and came up with a demo in two days. [Laughs.] And that was the core of the game. We were able to build a game around that proof of concept.

- David

If we're talking about initial resistance to fractals and things like imagined or real obstacles to making stuff, what about the more sort of VR things or AR things you were talking about before? Where did those initiatives come from?

- David

You mean from me?

- David

Yeah, or within the company.

- David

It wasn't anything in the company. This was the reason that I got into computers to begin with. Six years earlier I was brainstorming what I wanted to do next and this was the long-term vision, an interactive Disneyland and I realized, "Okay, if this is where I want to end up, I better learn about computers and games.”

I didn't want to open an arcade. That didn't seem like the right direction: "So how about if we do something that's more educational?" My wife was a teacher so we figured that would be a much better match with our interests and abilities. So, that's what we did. Through that, I taught myself programming and learned about writing games and then decided to write that book on computer animation which became this perfect match-up to get the Lucasfilm job because not only did it give me an entree into talking to the whizzes at the Lucasfilm Computer Division, but because of the Atari 800 connection -- the second half of the book was a tutorial on doing animation on an Atari 800. So I had this manuscript when I walked into my interview with Peter and said, "Here's what I've been doing for the last year, writing this book on how to do animation and programming games on the Atari 800."

I couldn't have done anything better if I had a magic mirror into the future. Plus the fact that I already had Lucasfilm's blessing on the book because they basically gave us a bunch of photos -- including Loren's first film on doing fractal flybys, Vol Libre. He gave me the film and I ended up putting frames in each corner of the pages so you can flip through the book and see his movie in motion like a flipbook. I was already someone they knew. So that was really cool.

When I first started working there I told Peter, "This was my dream, doing an interactive Disneyland."

And he said, "That's cool, but for now we're gonna be doing home computer games."

And then a few years later, as we were transitioning from more of a research group into more of a production group, Peter ended up leaving after Steve Arnold came on. Steve was our general manager for most of the time I was there, and he really loved the idea of location-based immersive entertainment. And he had been involved with a friend of his, Jordan Weisman. He did the Virtual Worlds Entertainment and Battletech. So he said, "Yeah, that sounds really cool. Let's focus on what we're doing now but maybe at some point we can do that."

So by 1990, we had grown from a small group of a few of us to 15 and then to 60 and by that point it was getting harder and harder for Steve to manage everybody. It was a very flat management structure.

Everyone was basically reporting to him. He asked me to give up doing games for a year and be the director of operations and help build up more of a hierarchy in management, so we actually had different heads of different groups who could then manage their departments -- a head of the art department who could manage all the artists and have a head of product support and one for QA, and I took over managing the programmers and designers, along with the new department heads, and it was really different than what I had been doing.

- David

Yeah.

- David

And I think I did okay. But I wasn't loving it very much. It took me out of the creative process for one, I wasn't really creating anymore.

- David

Well, you stick around at a place long enough and these are the sorts of things that end up happening.

- David

Yeah.

- David

What were the challenges of that beyond wanting to get back to being creative yourself? What do you remember?

- David

Well, the first part was that when he asked me to do this he said, "Do it for a year and at the end of the year then we'll do a location-based entertainment project.”

- David

Yeah.

- David

So I was like, "Okay, I can suffer through this to live my dreams." He was true to his word and I ended up hiring Lucy Bradshaw as my replacement and then got to go off and do this other project for two years. Lucy ended up as the senior vice president and general manager at Maxis.

- David

Right.

- David

But she loved managing at that level. That was much more the kind of thing she wanted to do.

For me, it was really problem-solving: "Where do we need more structure?" I worked with Steve. I mean, he didn't say, "Go off and do this on your own." It was a lot of talking about how to make this happen. We already had the collaborative culture in place at Lucasfilm, or at least our group: When we hired somebody into a specific area, everyone else who was already hired as a peer would interview that person. And there'd be this consensus about whether thumbs up or thumbs down, whether we felt it was a match, and then at the time Steve Arnold would have final say about whether to pick up that person or not. We would give recommendations and he would make the choice.

We knew we had to hire a bunch more programmers, specifically SCUMM programmers for the graphic adventures we were doing. That was part of my job, to work with HR at Lucasfilm to find a bunch of people who were young and brilliant and funny and could work together inside of our culture.

It was in that process where I hired Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman and those are probably the two that most people would know at this point. There were two batches of -- we called them SCUMMlets, and we had a one- or two-week SCUMM university training where Ron Gilbert would teach them the ins and outs of SCUMM programming and we'd watch what they were doing and the project leaders would then get their picks of which of these SCUMMlets they wanted working on their projects and in what roles.

That's how Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer ended up working with Ron on Monkey Island.

- David

Right.

As the company came to be more formalized and grew, how did that shift the beginning of game projects? You mentioned with Ballblazer and Fractalus how those were born of a more experimental mindset, but was that always the case at Lucas? Or more specifically, do you remember examples of how the beginnings of projects changed after the company had released more games?

- David

Most projects were driven by the game designers/project leaders. The designer would come up with a 1-2 page concept document and pass it around to the other designers. We’d all talk about it, and if there was consensus that it sounded like a good idea, they’d be given the go ahead to take it future, maybe into a 10-20 page design doc. After another review or two, it would move forward to being a planned game. Often we’d come up with several concept docs to see which one had the best response.

Other times, a project would be offered to us project leaders, and we’d have the option to say yes or no. Two I was involved with were Labyrinth and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, both Lucasfilm film productions that we had the option to adapt into films.

In the case of Maniac Mansion, that was Ron Gilbert’s and Gary Winnick’s concept, which they eventually invited me onto to do the SCUMM scripting.

- David

Well, I ask in part because I’m just curious how the industry came to resemble more what we see today with a certain aversion to creative risks. I think it’s always tempting to ‘blame the suits,’ but I remember stories about Sierra before Cedant acquired it, where Ken Williams would call, like, Al Lowe into his office and say, ‘Hey, make a cowboy game!’

- David

I think that’s pretty much how it was during the time I was there. We’d either come up with an idea on our own, or collaborate with another designer or artist. The decision was based on the peer review process, not by some marketing guy who ran focus groups trying to figure out if it would sell. This may have totally changed after I left, though. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, where most of the games that came out of LucasArts were Star Wars-based, I’d guess their freedom to create was greatly curtailed.

- David

Well, so, you've mentioned a lot of names so far, and I don't necessarily want to dwell on the well-known ones. But with George Lucas, sometimes it's a little absurd to think that George Lucas and Monkey Island are somehow related even though it’s right there in the name of the company. I've read all sorts of accounts about this, but how closely was George Lucas involved with the games group?

- David

Uh, pretty much not. [Laughs.]

- David

[Laughs.]

- David

I mean, clearly, he was involved on some level because he gave the thumbs up to the games group, and he would get ongoing reports from Steve Arnold. But I think Steve Arnold knew that George -- and this is apparent from how much he hung around us, which was pretty much not at all -- was doing this more for his vision of the future and that gaming and films were kind of on this convergent course, an intersection where games would be very film-like and you couldn't really tell the difference. I think he just wanted that knowhow inside of the company. I mean, he was doing a bunch of stuff which was very experimental. That was kind of his reason to do games. He was also very interested in education and wanted a part of bringing games to learning. The only two games that he had any input on, really, were the first two games we did. He came in --

- David

In the early '80s?

- David

Yeah, really, just Ballblazer and Rescue. And he came in while we were in pre-beta and I demoed Rescue to him and Dave Levine demoed Ballblazer and had a 20-minute sit down with him talking about the game and him giving us feedback. It was hugely valuable for me because out of that came a couple of really key things that ended up in the game, which probably made the game way more memorable than just a flight game.

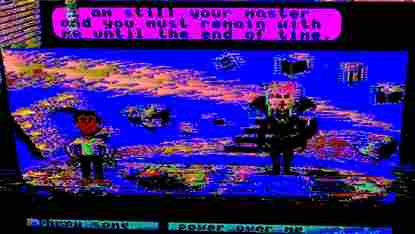

One was the Jaggi monster pop-up idea and the other was making sure that there was a fire button -- two things. [Laughs.] At least the fire button probably would have happened through some other means, through testing and seeing how people liked it. But the idea of adding this level of tension of not knowing when this pilot you're trying to rescue was actually going to be a pilot or a monster -- that just totally transformed the game. People still write to me describing the first time they played the game when a Jaggi monster popped up and what their reaction was, because it was kept hidden. It wasn't in the documentation. It wasn't in the marketing material. Other than word of mouth, people generally didn't know about it. We also made sure it didn't happen for the first few hours of gameplay.

- David

That's an interesting point. That kinda makes sense, that Lucas would see the games group as a way to have skin in the game or to also see it as research for what might be ahead for what he's doing. I mean, you were there for about 10 years. Did you get a sense of how the games, through osmosis, impacted him or the things Lucas was doing in general?

- David

Not too much. For the time that I was at LucasArts -- I was there for the first eight years -- we weren't allowed to do Star Wars games. So there really wasn't a full docket to let us use that. The first Star Wars game I got to do was for the Mirage project. That was a different space. I think part of it or most of it was, at least up to that point, that Star Wars had already been licensed to other companies. Atari had an exclusive license for arcade. Parker Bros. had the exclusive license for home entertainment. And at the time, initially, it was like the Atari VCS system. I think there were a few other ones that might have gotten licensed. But, you know it was always, pay us X millions of dollars -- whatever it was. That was guaranteed income. Where, if he had to pay for production and also assume the risk of whether it would sell or not -- probably from a financial point of view it didn't make a lot of sense.

And that totally changed in the '90s and beyond that, where it eventually almost pretty much the only thing that they did at LucasArts.

- David

Yeah. That's possibly what a lot of people mainly remember, that Lucas made a lot of games and then over the course of the '90s they became very reliant on Star Wars projects. I think, in fairness, people do remember more than that. There were a lot of non-Star Wars games in the '90s that just ended up being canceled or were unsuccessful. Obviously you weren't there, but what changed about the market and the way LucasArts did business where Star Wars started to become the focus?

- David

I'm not sure. Some speculation was that I think they saw how much more money they were making from the initial Star Wars games that we were releasing and it just seemed like a much better bet to do a big Star Wars game than to do Day of the Tentacle or something, which was totally created from our own IP or our own ideas.

- David

Yeah.

- David

I think our graphic-adventure games -- my understanding was that while they were popular within the graphic-adventure audience, that was limited. And as the games started becoming more and more expensive -- the production values had been getting higher and higher and the cost to do them kept on going up -- I don't think they were getting enough of a return on their investment in terms of sales. So, I think that's why in 2004 or 2005 or whatever, that's when they started killing a bunch of their adventure game projects. So, I think it was basically just ROI. It was very much, by that point, run like a business. They had to make a profit.

There was also a lot of changes of direction -- every few years they would hire a new head of LucasArts. People generally lasted two to three years in that position and then, for whatever reason, either George would change his mind about what he wanted or the person left -- I don't know exactly. And the directions would keep on shifting. Sometimes they'd say, "We have to do more Star Wars stuff. We have to do this." When the first trilogy came out -- the films one, two, and three, however you want to call it -- I'm sure that's part of the focus to, you know, put all the energy in the company towards building up this license again. That might have been why they were doing a lot more Star Wars games then. I also understand that later on I think they were doing a couple of the really large Star Wars games and George was much more involved with the story and the whole concept to the point that he might have made changes to the designs in a way that really hugely impacted the production schedule and costs.

- David

I know that you were not there for that transition, but this is something that I am curious in general about. Were teams happy with the projects that they were being given to do if, like you, they had not really signed on to do a lot of Star Wars games but they found out that's what their job had become?

- David

Yeah, I'm not sure. I came to the company because I wanted to do Star Wars games and was really disappointed after I got there that we couldn't because the licenses were gone. Rescue on Fractalus! was supposed to be a Star Wars game when I first conceived of it. I kind of wanted to capture the feeling of being in an X-wing and speeding through an environment. But in retrospect, it was a huge benefit to us to not have that as part of it because we didn't have it as a crutch. We were forced to be creative on our own.

- David

Right.

- David

And because we weren't doing Star Wars, George wasn't really interested in what we were doing. We did do a couple of film-based games in the '80s. One was Labyrinth, which was a Lucasfilm production, and the other was Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. And in both cases, we were mostly on our own -- other than wanting to keep as close to the story as possible, no one said, "No, you can't do that. That's not okay." We actually had a meeting with George and Steven Spielberg before we started Indy, we asked them, "How far could we go off story if we wanted to? Could we kill Indy?"

- David

[Laughs.]

- David

They said, "Yeah, do whatever you want."

- David

Really.

- David

Yeah. A lot of freedom.

- David

Is that just because those are Lucas properties? I always would expect in a branded thing where you're working in someone else's world, you'd be falling under a lot more scrutiny.

- David

Yeah. And that's for sure the case. One of the functions that the games group had early on was to review the games that Lucas had licensed to other companies, to make sure that they matched the Star Wars universe. I remember looking at a couple of games and saying, "No, this doesn't make sense and this should change and that should change." But -- I guess Steven Spielberg was a gamer and he was much happier to help us push it in different directions. In fact, he wanted us to take it to other countries and other continents, way bigger than we could actually do. So, he was happy for us to push it out.

- David

Do you remember an instance where you, within the group, decided or defined the rules of what was going too far with Indiana Jones? Obviously for a LucasArts game, to kill the main character is unusual. But do you remember cases where you decided to pull yourselves back a bit on Indy?

- David

Not too much. Because we were on a tight schedule, we had three project leader designers on that game. We had Noah Falstein, Ron Gilbert, and myself. So, each of us had slightly different or in some cases majorly different senses of humor and where we wanted to take it. Ron was trying to go much more flip and tongue-in-check. Noah was trying to be maybe a little closer to the story. There was one instance where Ron wrote the end-game sequence where you're trying to leave with the grail cup and there's this earthquake and everything goes to hell. His dialog was really funny tongue-in-cheek stuff. I thought it was placeholder because it was so irreverent.

At the same time, Noah was writing dialog which was closer to the movie.

He said, "Okay, here's the dialog."

I said, "Wait a second. Ron already had his here."

I said, "Ron, this is placeholder, right?"

He says, "No. I didn't mean this to be placeholder. This is what I want to have in the game."

So you had two very divergent ways to communicate that ending, with one being fairly serious and one being very tongue-in-cheek. They both wanted theirs in and they both had reasons.

So, my solution was to randomly choose one or the other. They both double-checked my random-number selection process to make sure it was evenly random and so it could go one way or the other. They're both in there. But, other than that, I think -- we've definitely kept it funnier in a lot of ways than the film was. There was a lot more Lucasfilm Games irreverence happening throughout the game.

- David

You mentioned that there was some turnover of heads of production or people spearheading vision. Why was there so much turnover with that? That was during the '90s?

- David

Yeah, so, that was after I left.

- David

Yeah, I thought so. I hate to ask you questions about after you left.

- David

Yeah. I don't know. I know for sure it was sometimes a George decision that changed the direction. Like, "We need to focus more on this. We need to focus more on that." There was a period from 2008 to 2010 when Darrell Rodriguez was the president. He loved the old games. He loved the history of the company. Around that time we hit the 25th anniversary of LucasArts and we ended up doing this company meeting where myself and 10 other Lucasfilm Games members from the early '80s gave a presentation to the whole company to talk about the roots, where we came from, what was happening in the '80s, what the games were, what our directive had been. For a lot of the people -- some of the people hadn't been born at the time that we started working on Lucasfilm Games. [Laughs.] We asked how many people are under 25 years old and 30 people raised their hands. So, they had no idea why things were done the way they were for whatever part of the culture stayed there with the company for all those years. So that was really interesting.

Darrell was also really interested in reviving or re-releasing some of the old games. I think that was during the period they did a relaunch of Monkey Island, maybe the first two games, with higher res graphics. All that was happening then, and I was actually talking to them about the idea of doing a new version of Rescue on Fractalus! using current technology. That was going really well and then he got fired. [Laughs.] They brought in someone else and they closed all the projects for all the classic stuff and it all stopped. I think a lot of it amounted to George changing his mind, that he wanted to go in a different direction.

- David

You've been in the industry since the '70s, and I am curious about the advent of the enthusiast press and also there just being more and more media outlets doing press on videogames. How did the process of the company getting involved with doing games -- how did that change things at the company and with productions? Or did it not change anything?

- David

I don't think so. I know there were some stories that came out right when we first started up the Games Group and I think we went quiet and the next PR really was around the launch of the first two games. They kinda did that pretty big. We ended up doing kind of a press conference at Lucasfilm. There was one of the screening rooms we had there, which maybe holds 150 people, and it was filled up with reporters and film cameras and we all had some media training so we could talk to them. We did a couple of videos which I actually have on my website, which were shown using footage from the two games and we placed an audio soundtrack on top of it. I think after that, it was more press-release based. We were always at the shows like CES and that changed to other shows. But, no, it really wasn't until -- Maniac Mansion was the first game that we published ourselves. Up until that point, all the games were published through a partner like Epyx or Activision or some other company. So that was probably when we took it over ourselves.

- David

So, I may have gleaned from our conversation a bit and looking at your website and résumé, but why did you choose to leave Lucas?

- David

It was after the two years I was working on this Mirage project. Steve Arnold was a huge proponent for doing it. He was our champion, really. He was the one who got it launched. He ended up leaving to go work for Bill Gates. There wasn't anyone inside of upper management who was passionate about what we were doing. That, combined with some realities about what the costs were gonna be to actually produce the whole system, I think there was this surprise that happened when we actually sat down with Hughes about what the cost would be, how to price these things out. We were coming from a film-company point of view, where it's all based on actual production. They were coming from a defense-contractor point of view, where everything in the whole company is included in some way or another. [Laughs.] Lucasfilm decided to just close down the project and sign it over to Hughes and let them try to sell it themselves. I don't know whether that hurt the project because the Lucasfilm name wasn't attached to it anymore or they just couldn't find anyone who would actually pay that kind of money to install these systems.

But it closed down. So, when our group closed down, I left. At the time, I said, "Well, should I try to go back to games, to LucasArts from this separate group?" Like I said, it just felt like I couldn't go back to that. Not after a taste of fully immersive entertainment.

- David

Well, you had said, you went and worked on other projects much more geared towards kids. I think you said you were interested in ways that games can sort of be more of an experience than a diversion. Am I misremembering? Didn't you work on a multimedia game with Neal Stephenson shortly after this time?

- David

Yeah, that was a game that I worked on that never actually got completed. We went through the design process and early production.

- David

Well, he had something like that happen recently, which I assume you heard about?

Yeah, was that the thing with the sword-fighting?

Yeah, it was the sword-fighting Kickstarter thing. They worked on it for two years and decided it wasn't fun.

- David

Ah. So, this game, he had this idea and I was trying to turn it to game design and it just kind of -- I just couldn't get it to happen and I ended up leaving the project by choice. Then I heard afterwards that they just couldn't make it happen. They couldn't solve it. They couldn't get it to happen, either, so I guess it wasn't just me.

- David

Yeah.

- David

I loved working with him. He was great. It was just too abstract as a concept.

- David

What did you notice was different about the way someone like Neal Stephenson -- someone outside the game industry -- approached making games?

- David

I think, from his point of view, he had this idea which was really much more of a story and we were trying to figure out how to turn that into a game. It could have been a screenplay, almost. Maybe the direction we took was not the right approach, but -- I mean, I also had experience working with author Orson Scott Card. That was really fun. He was hired as a creative advisor for several projects. He actually wrote the insult sword-fighting text for Monkey Island. He worked with me on the Mirage project, where I'd have the concept for the game and he would write up a two- or three-page scenario describing a family going to this theme park and playing this game, what it would be like, in a great story way. He was really fun to bounce ideas off of. A really creative guy. And then for Labyrinth, we spent a week in London brainstorming with Douglas Adams on the game. because he was friends with Jim Henson, who was the producer of the movie. That was really crazy. I got to work with some really high-powered and brilliantly creative individuals. The trick is that in most cases they weren't game players, so we had to be the ones who could take their concepts and their ideas and throw away the ones that just weren't practical or weren't gonna be fun and find the ones that were and work together on those.

- David

Do any of these unfeasible ideas from a Stephenson or an Adams or even a Card still stick out in your mind from this period of time? You say they weren’t necessarily game players, but what did you glean they felt or thought was really important to games or that they thought would be fun for people playing games and why?

- David

Not really. It was more the point of view that wasn’t workable. Filmmakers, for example, often think very linearly, and that doesn’t work in a game where the player doesn’t want to fill totally constrained from making their own choices and decisions. Or on the other end, they’d want to open up the game so much, with so many branching possibilities that it would have been impossible to complete creating the game in the same century.

- David

But that's all interesting because some of the stuff from the '90s, there were other games by other companies. I don't know if these names will sound familiar to you, but there was a game called The Dark Eye and another called I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream. It seemed like there were more attempts at bridging gaps within games to other mediums. Is it just me who feels like that's a much more rare thing now?

- David

Yeah. I think part of it was -- especially in the '90s, CD-ROMs were now available and so the amount of --

- David

- David

Yeah. Yeah.

- David

Peter Gabriel.

- David

Right. Right. Now you have enough storage where you can actually put much more content and everyone thought this was the next big thing. When this happened, there were a lot of filmmakers and producers who got involved with doing stuff like this that couldn't really crack the interactive part. As I said, they were linear storytellers and they just couldn't make the leap, and then the whole thing kinda collapsed in the end.

- David

That was Lucas was hoping to get intel on, right? The way games can impact storytelling or to make them more film-like?

- David

Yeah, I think so. To bring both in, the high production values but keep it interactive. You really need the game background and experience to know what could work and what doesn't work and I think it's really tough to make the leap. The only one I know who did a really good job with that would be Hal Barwood, who was at LucasArts for a number of years. He was a film director and writer before. He was a friend of George's. But he also taught himself Assembly language and was doing Apple II games on his own. He ended up becoming this advisor for us early in the '80s and then he just ended up joining us as a game designer and project leader. He could speak both languages. He understood games and he understood films. I think that was hugely rare, someone who could do both equally well.

- David

Do you feel that's still rare?

- David

I do think it’s rare. You have to be a brilliant storyteller, and also be a big game player or game designer. Maybe it’s two different parts of the brain? I’m sure there are others… I know there are a lot of game designers who really want to be filmmakers, but maybe it’s rare for it to go in the other direction -- unless they’re just trying to cash in on games, and not a true lover of them.

- David

What seems weird to you about the game industry and what it has become? Or, to put it another way, what'd you imagine the game industry in 2015 would look like when you were first getting started?

- David

When I was first getting started, I thought we would have this full-blown interactive Disneyland vibe in 15 to 20 years. Clearly I was way off on that. We don't have it yet.

It's interesting to see how we thought VR was the big thing in 1992 and that it just totally died back then because, again, it was a combination of too expensive and too clunky. Now there's a resurgence. I think this time there's a much better chance it's gonna go more mainstream. But there's still some major issues to solve in terms of motion sickness, for one. [Laughs.] I can't do most of them myself just because it makes me sick after a short time depending on how the game is structured. But I think that's going to continue to evolve. It may take another 20 or 30 years, I don't know, until we have that kind of environmental gaming with either doing an AR-type overlay with headwear that gives you 3D overlays with perfect registration. I went to Universal Studios last December and -- it's the one in Florida, where I got to go to The Wizarding World of Harry Potter.

- David

Is that the one with the bar where you get the candy beer?

- David

Oh yeah, you can get the butter beer.

- David

Yes. I believe I've been there.

- David

Yes, so, it's a huge environment with all the streets and everything. I don't know if you've been there in the last year or two, the last few years?

- David

Uh, maybe it was two or three years ago. Yeah.

- David

There are two whole different areas now. There's the Hogwarts/Hogsmeade area and there's also the Diagon Alley area, which is the London-centric one. Both are just brilliant. Really, really impressive. I started thinking about how you could do an AR-type experience there where you're wearing some kind of headset and can see ghosts and magical creatures, and if you're carrying a wand, you can cast a spell and actually see the bolt of energy firing across to wherever you're aiming it out and have amazing things happen in this great environment. So all the 3D environment structure is already there, but all the interactive stuff would be through your headset and some portable or wireless computer.

- David

Do you get a sense that this sort of whimsy you're talking about, do we see less of that from industry videogames nowadays?

- David

Mmm, you're probably asking the wrong person since I don't play many games. [Laughs.] I really haven't played much in the way of adventure games for a while, so I'm probably out of it.

- David

Well, it makes sense. You did live that life for quite a while.

- David

Yeah, but even then I didn't play a whole lot of outside games. Every once in awhile I'd find a game that some people would say, "You have to play this." I'd play through and, you know, spend 40 hours or whatever until I got through it or seen enough to understand what it had to offer. But one of the reasons I don't do it is I know that it would be a huge time suck for me where I'd end up compulsively trying to finish the whole thing. [Laughs.] I don't have time for that right now.

- David

I think I saw on your LinkedIn that you joined the Producers Guild of America a few years ago? Is that right?

- David

Yeah.

- David

What do organizations like those that are further away from the game industry, what is their perception of videogames and the game industry? Or does it not really come up in your conversations with them?

- David

Joining the Producers Guild came about because a couple of friends of mine who were in the game industry joined. They basically said, "Hey, you can get free screeners. You can go to screenings. This is the season now where I'm getting all these DVDs in the mail of current movies that I get to watch at home so I can vote for the Academy Awards." Plus I can go to movies for free and I always like that and there are all these screenings that are happening for the last few months. I can some at Skywalker Ranch and some at ILM. This happened all the time when I worked for Lucasfilm, and I really missed them. The best screenings are when they have the film’s producer or the director there, talking about it and answering questions after we’ve watched the film. There's this New Media part of the Producers Guild, which is specifically for digital media and interactive media. It has different standards than having to have produced a film. There aren't a whole lot of New Media members yet. There are more here in the Bay Area, and if I were looking for jobs, it would probably be a great way to network. But that's not something I'm looking for. We have meetings and can talk about relevant issues, or they might demo new, breaking technology. Not working at a company, I don't have the water-cooler talk that you would when you're going out to lunch with people all the time. So, it's a great way to connect with other people in the industry.

But the question was: Who would be interested in this other than someone who came from a Lucasfilm or LucasArts, who already had the experience of being inside the industry and would still like to have their connection to the film industry. So, yeah, I'm enjoying it but I think it's probably not going to have this widespread interest to people who either are already at a large company like Electronic Arts, why would there even be a reason to join this unless you loved movies to the point where you want to go to screenings and get screeners?

- David

Before we got started I briefly mentioned Gamergate, which you didn't really react to. Have you heard of --

- David

I did hear about it and I did read some stuff about it and I could read enough to know that emotions were really high on both sides. I'm definitely on the side that any kind of misogynistic attitudes should be eliminated and that women game designers and women -- any position that a guy has in the industry should be open, with gender making no difference. I wish there were a lot more women game designers out there so we'd have a broader variety of games.

- David

Given your experience with the industry since the '70s and '80s, did you ever hear any notions about that sort of attitude being prevalent or did you ever run into it?

- David

Not too much. In fact, back when I was director of operations, I was specifically looking for an even number of men and women that we were hiring for positions. And we did, as much as we could. We hired women SCUMMlets as well as men. And across the other areas in art and other departments -- there weren't many women programmers. I think they just weren't available. So, I think Lucas tends to be a pretty open company. Or at least it was at the time I was there.

- David

Do you remember anything about the audience in those days being very aggressive or angry or some of the things you see a little bit more today?

- David

No, I don't think so. I mean, I'm pretty much like, "What the fuck? What's going on with these people?" You know, my wife is a game designer. She's done game design, too. We often collaborate on projects and we have different takes on things, but we know each other's strengths and weaknesses. We really work well together. We got to work together on some Disney projects. We actually designed together some interactive experiences for a couple of the Asia Disney parks. One of them actually got implemented. And so, that was the closest I got to doing an interactive Disney thing, was actually to do one. [Laughs.]

I might be missing some of the point of it. If the point is that women shouldn't be doing this, I'm like, "Huh? I don't get this." I live in Marin County. It's probably one of the most liberal counties in the country. And that's where Lucasfilm was based, in San Francisco, which is probably even more liberal. We're essentially in a bubble, so seeing all this anger and negativity, it's like, "Where is this coming from?" It's really hard for me to relate to it because it's so far from my daily point of view and consciousness. For my whole life, really.

I finished watching Jessica Jones on Netflix. The showrunner, the producer/creator is a woman, and she intentionally directed it in a certain direction so her superhero is not wearing short skirts and not using sex to interrogate people, and really going for a strong female character point of view. Very complex person and background and if you haven't seen it yet, it's the best thing I've seen on TV in years other than Game of Thrones. I think it just gets stronger through the whole series.

It was just really good. It starts strong and all of a sudden I feel like, "Holy fuck. It just went to this whole other level." They shifted it but they didn't. They opened a whole door to another level of possibility, and then that happens several times through the whole series. It's smart. It's really really well-written and plotted. I was just so impressed with it. It's really interesting that this is on Netflix as opposed to cable or, for sure, on network television.

It's harder to watch other shows now because my standards have been raised. Look at some of the interviews with Melissa Rosenberg, the showrunner, how she intentionally crafted it. She did not want to show any rape scenes or anything like that. She felt like that turns something which is a violent act into titillation by showing it. She had a very strong point of view about how she wanted to present the series and the show. And then, of course, they had a superb cast and production values were really good, too, so I loved it!

- David

What do you think videogames have accomplished?

- David

In terms of the games that I've been connected to, I think that they can help you think in ways that you wouldn't normally think. If you look at graphic-adventure games -- I think they really change how you would approach problem solving and approaching issues in everyday life theoretically. I've definitely had the experience where in real life I was trying to find my way around some place and having played adventure games and being able to move around an environment, it definitely helped exercise some brain muscle in terms of finding my way around something in the real world.

I don't want to talk about the negative stuff because I don't play that kind of games. I'm not really into shoot-'em-up-type stuff. I think that would be a negative impact to the degree that playing a game where you're going around shooting people all the time could desensitize yourself to doing that in real life. I think that might be possible in some cases. Most people can separate reality from fantasy. I've had the experience of coming out of a movie like Star Wars or a movie where you're flying around at really high speeds in a plane or a ship or a car and getting behind the wheel of my own car and having this feeling like, "Okay! Now I can go around corners really fast." There's that impulse, although even if you never act on it it kind of takes you back. I think people can separate the two. Most people can. But for some people, maybe not.

Thanks for reading! Please consider supporting my work directly.

Send a tip to David